| Part three- Healy and the King's Chamber sound mix.

Part two:

As we started our trek into Upper Egypt, Hamza took me aside and said. Now,Mickey, it is time for you to surrender. This doesn't mean

to give up, to go fast or go slow, but to go with the natural flow of

the desert. It is so big and you are so small. Soon, the loudest thing

you will hear will be the sound of silence.

Using Aswan as our base, we travelled to Kom Ombo, the area where

many of the 250,OOO Nubian families were relocated following the construction

of the Aswan Dam. The dam was built In 1965 as the result of an agreement

between then -Presldent Nassar and the Soviet Union because all of Nubia

was destined to be flooded. In the wake of the flood, the Nubians were

ruthlessly moved out of their ancestral homeland and relocated in a

barren wasteland many miles from the Nile. Nassar claimed the dam was

a modern miracle. For the Nubians it was devastating. Uprooted

from their spacious homes along the river where they were farmers and

fishermen, they were relocated in government-issue houses, small and

poorly planned. They were minimally compensated for their former homes

and unable to bring most of their possessions, animals, etc from old

Nubia. It took four years in New Nubia to establish irrigation canals

from the Nile so they could begin to plant sugar cane, date palms, and

fig trees for harvest and support of their families. Part of their culture

and their hearts were lost under the water of Lake Nassar, but the spirit

and warmth of the people we met will long be an inspiration and source

of strength.

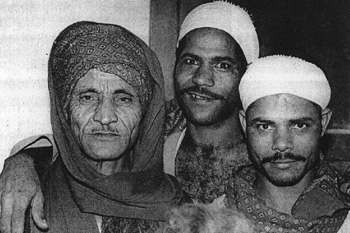

When we arrived in Hamza's village, called Tuska, he was greeted as a home coming prince. He hadn't been there in four years, so all his brothers, cousins, aunts, and uncles were there in force. After the social graces of tea, handshaking and laughter, we moved outside into the courtyard of one of their homes and a cousin of Hamza's brought in a Cairo newspaper with a photo of Hamza and me playing our tars at the lost concert. The men were happy to learn that I play tar, since it is their native instrument. The desert is the tar's home, and in this dry air it speaks with a bell-like tone-crisp and sharp in its overtones. The tar is a single stretched skin,14 inches in diameter with a four-inch laminated shell one quarter inch thick. It looks Iike a large tambourine without jingles. The drum has been used in Nubia since Pharaonic times and is even used by the women for such practical purposes as sifting grains. But only the men play it as an instrument. One by one, the master tarists of the village showed themselves. First, the old blind tar maker of the village took my tar and felt the outside wood and skin, marvelling at the uncommonly smooth finish. My tar was made by a friend of Hamza's in San Francisco and the craftsmanship is exceptional. After further checking the outside of the drum, the man began to scratch and sniff the inside of the skin to determine the type of skin it was, Then -he played it, and the quickness of the drum surprised him. He then handed me the drum with a gesture to play. This was a tough act to follow, but having studied the tar for three years with Hamza, I took a deep breath and started to play. After a minute, their faces lit up and the children started hand clapping; the women gathered around, the men brought out their tars and a party was underway.

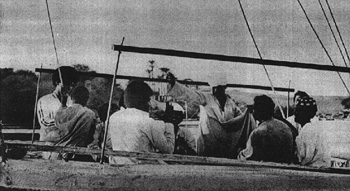

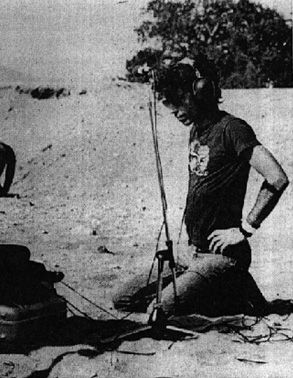

challenge. For instance, one recording in Aswan involved taping and filming the crew of a felucca boat cruising down the Nile while the boatmen sang songs of the river, their lives, and their work on boats. The recordlng was made using two Sennheisser shotgun condenser mikes whose tight pattern allowed us to record while travelling alongside their boat in another vessel. In this case, the men were completely at ease, as there were no visible microphones or equipment in their way. Travelling with Hamza, our musical adventures went smoothly. Then was one night in Kom Ombo when the whole village turned out to honour Hamza. A Iarge courtyard held 300 people -young and old, dancing, singing, clapping. After everyone settled down a bit, it became obvious where to place the Neumann KM84 microphones and Raafat with his camera. It didn't seem natural to direct the musicians for the purpose of recording, so we allowed them to gravitate to the place where they felt most comfortable. Once the mikes were set and the Nagra assembled in an inconspicuous corner, there was nothing Ieft to do but fill my hash-pipe, roll the tape, and enjoy. An interesting situation occurred in Alexandria at the seaside home of Hani Sabet, an Egyptian businessman and friend. Hamza's interests lie in the reproduction of American and domestic music on quality cassettes for distribution in Egypt, Italy, and the Middle East. Since there are few phonographs in Egypt, cassettes have emerged as the principal music medium. Being part of the music scene in Alexandria he arranged a grand party in my honour, for me to hear and record the Saiigrean and Bedouin music of the North. Hani invited his,friends musicians and townsfolk alike for a feast of freshly slaughtered lamb, fish from the Mediterranean, and wine. Hani provided an ample amount of hashish and "hubbly-bubbly" pipes for the party. ''Hubbly-bubbly'' is the name given to the water pipe, by virtue of the sound it makes as you smoke it. The hashish, mixed with a sweet tasting tobacco, is drawn through a narrow two foot long bamboo rod, having been mellowed and cooled by the water in the base. We all sat to smoke, and as I played and admired their drums, we set the mood of friendshlp from drummer to drummer. Finally at ease, the first group, Saiigeans from Upper Egypt, began to play in the courtyard. These musicians take a long time in developing their ideas, which extend over many hours.There is no reason to hurry. They state their theme, play a variation, restate the theme, and offer more variations. They will play for a couple of hours, stop, smoke lots of hubbly-bubbly, and laugh and talk until they play again, returning to the theme when they left off. Most recordings I have heard of African music have been technically poor,made on small machines by anthropologists, mainly as an afterthought. This trip gave us the opportunity to record this music -these elusive sounds from the "other side"-in true stereo.

Some of these tapes have found their way onto disc form and are distributed by small companies, but mostly, they are preserved in my locker for posterity, not unlike fine vintage wines. Without MERT and the Assistance of Bret Cohen, John Cutler, and Jerilyln Brandelius, the excursion to Upper Egypt could not have taken place, and we would have been unable to seek out and record this ancient music which holds a special place in my heart. Part three- Healy and the King's Chamber sound mix.

|

|||||||||||||

| |